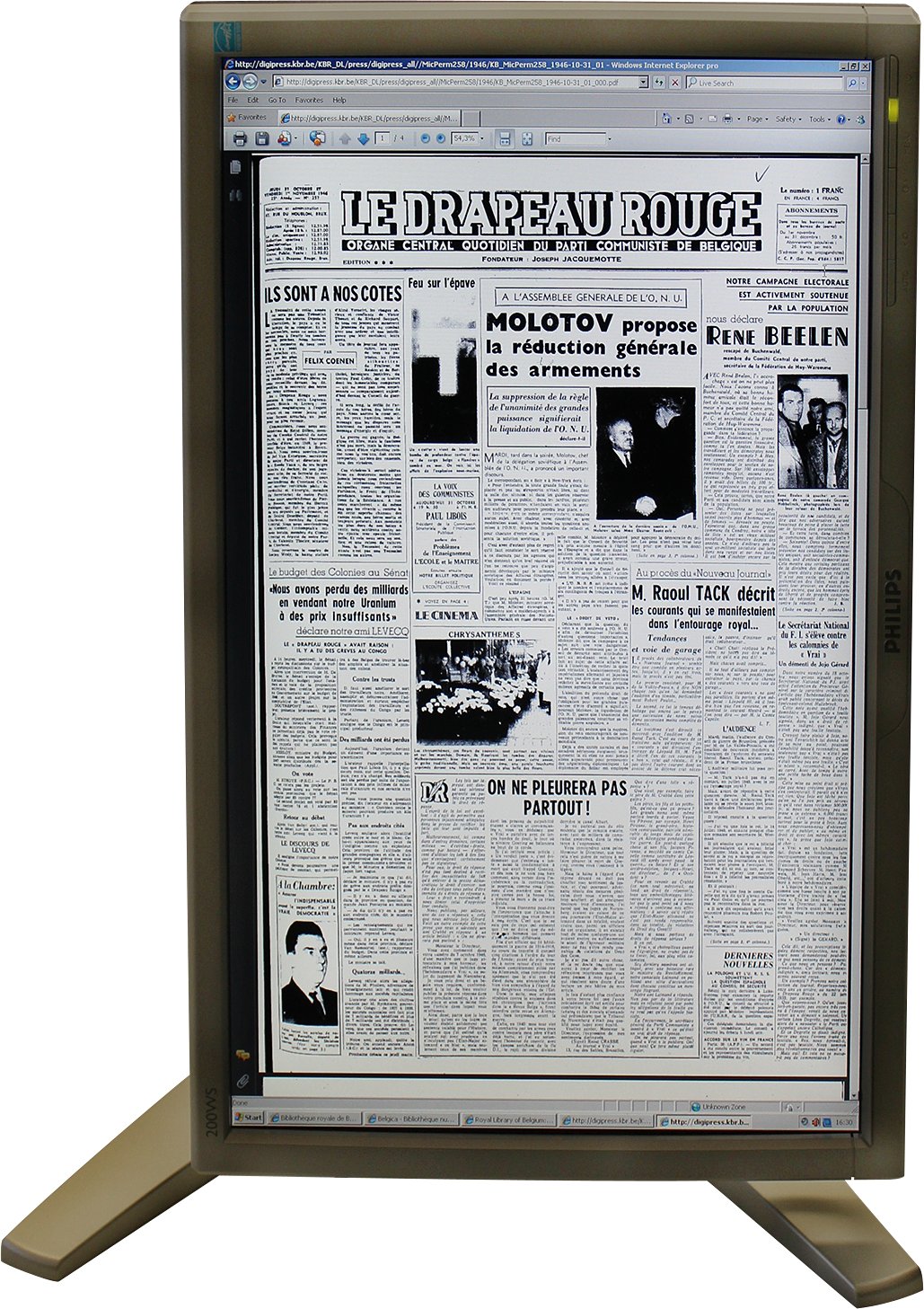

This computer is situated in Belgium’s Royal Library. It offers you access to an internal network of 300.000 pages of Belgian periodicals, produced between 1831 an 1945. It has no access to internet, no usb ports, and no connection to a printer.

If the library allows any digital distribution of the materials outside of the library walls they risk claims of copyright holders.

During Public Domain Day (NL) Librarian Marc D'Hoore explains: determining the authorship of a newspaper is difficult. Much of the work is anonymous or pseudononymous. There are not always clear contracts between the publishers and the authors. You do not know who owns the copyright, and you do not know when it will pass into the public domain.

Because of its mission of preservation, the Library needed to scan these materials—the paper is of extremely poor quality and disintegrating. But the Library also has a mission to facilitate access to its materials in any way it can.

Digitalisation seems to offer a great potential to make the material from the collections more accessible. Once scanned, material can be indexed, and put online, and be available to everyone with an internet connection. In potential. In reality, the Royal Library can not do this, because it would open itself to all kinds of claims of damages by copyright holders.

Reply

The public domain day highlighted work of authors that have recently fallen into the public domain. Copyright is death + 70 years, which means that the work of those who died in 1942 becomes public domain the 1st of january 2013.

source: http://constantvzw.org/publicdomainday/

Reply

Effictively, we are in the middle of the Second World War right now . In 1942, Bruno Schulz has been shot in Drohobycz Ghetto. Alexander Belyayev has died of starvation in a nazi occupied Soviet town. Olena Teliha is executed by the Gestapo in Kiev. Jakob van Hoddis has been deported to Sobibor along with the rest of the patients (and staff) of the sanotorium for the mentally ill where he resides. Daniil Kharms has been imprisoned in a psychiatric ward in Leningrad by the Soviet regime, and dies of starvation after the nazi blockade of the city.

Reply

At the event in the Library, they mainly highlight the author Neel Doff, which at first I think I’ve never heard of—and then I realise her work provided the basis for the iconic Dutch 1970ies movie Keetje Tippel, by Paul Verhoeven.

Femke Snelting and An Mertens of Constant VZW provide a generative novel based on the work of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, among others.

Reply

Keetje Tippel, the movie, will still stay under copyright for the rest of my lifetime. But I would love the show you the one crucial scene in which Paul Verhoeven brilliantly catches the essence Dutch 70ies cinema and his own visual language…

Reply

Reply

In the meantime the volunteers of Gutenberg have had the time to prepare a digital edition of Ulysses. More accessible than ever, so it’s more easy than ever to not finish it :)

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4300/4300-h/4300-h.htm

Reply